It’s the question that every nine-year old asks (and every adult wants to ask but is too embarrassed)–how do astronauts go to the bathroom in outer space? The answer is surprisingly complex.

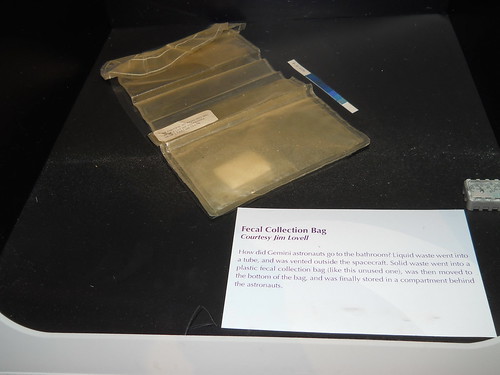

Fecal collection bag. Adler Planetarium, Chicago

According to the flight profile, America’s first astronaut in space, Alan Shepard, didn’t need to make any bathroom plans. The Redstone booster rocket being used for his Mercury mission aboard the capsule Freedom 7 was not powerful enough to reach orbit, and his entire flight would last only 15 minutes as he popped up, floated weightless in space for about five minutes, then fall back down to Earth. Sadly for him, however, things did not work as planned. A series of technical problems delayed his launch, and he ended up sitting strapped into his seat for over four hours. And he had to “go”. Desperately, he switched to a private channel to ground control (not heard by the public) and asked what to do. Ground control now faced a stark choice. It would take hours to open up the hatch, get Shepard out of his suit, let him pee, then get him re-suited and back into the capsule. The only other choice was to let him pee inside the suit, but it hadn’t been designed for that, and the liquid might cause the internal electronic circuits to short out. The answer crackled back from Mission Control: “Do it in the suit.” And as feared, most of the medical sensors intended to monitor Shepard’s heart and breathing were shorted out.

For the next mission, Liberty Bell 7 flown by Gus Grissom, a solution to the “peeing” problem was hastily improvised: a pair of rubber underpants was worn under the suit, and it had a little pocket in it to collect any liquid waste. And what about, uh, solid waste? Well, it was hoped that the traditional astronaut pre-launch breakfast of steak and eggs, selected because it was “low-residue”, would take care of that.

Such a solution would not work for the much-longer orbital Mercury missions, however. The early Mercury-Atlas flights would last several hours, and the later flights would last for days, as would the planned Gemini and Apollo missions. So all the astronauts were now provided with a condomlike device that was held in place by a belt, and had a plastic-bag collector at the front. If all went well, the bag was filled with urine and then sealed shut and stored to be returned to Earth, where samples were examined by medical staff. If all did not go well, little drops of urine would escape and float around in the zero-gravity environment, and after a few days the inside of the spaceship would smell like a porta-potty. It could also present a safety problem: during Gordon Cooper’s Mercury flight, it was determined that urine droplets had worked their way into the spacecraft’s electronic circuitry, causing the failure of several systems.

Oddly, the astronauts all pee’d a much larger amount at a time in space than they did on Earth. The reason was gravity. On Earth, as the bladder gets about half full, the weight of the liquid gathering in the bottom stretches the bladder walls, which signals the brain “time to pee”. But in zero-gravity, there is no such signal, and the bladder fills almost to the top before it begins stretching the walls and triggering the nerve signals.

In the Apollo spacecraft, a new system was devised to handle liquid waste. A tube was provided that was worn like a condom. A hose ran to a valve that opened to space. The idea was that you pee’d in the tube, and all the liquid would be vented outside the spaceship, where it formed ice crystals and floated away. But it wasn’t quite that straightforward. The suction created by being exposed to the vacuum often pulled you in, and when the valve device closed it would sometimes catch a part of you. Ow. And if you tried to avoid that by pulling out early, it often released droplets of urine to float freely in the cabin.

So, what about the solids? The solution here was even more low-tech. The Mercury, Gemini and Apollo astronauts were all given “fecal collection bags”. These were large plastic bags that were provided with a wide peel-away sticky rim. You had to drop your pants, attach the sticky rim to your butt, then do your business. However, there was an additional step you had to do: since in a zero-gravity environment nothing “drops”–the plastic bag had a finger-sized pocket extending inside, so you could put your finger in there and use it to detach anything that needed to be detached. Once you were finished, you then had to open a little vial of blue germicide liquid and pour that into the fecal bag, seal it shut, then carefully knead the contents to mix in the germicide. (If you weren’t thorough enough, methane-releasing bacteria could produce enough pressure inside the bag to make it pop like a balloon and scatter its contents.) Then the bag went into storage. Don’t poke any holes in it. The whole process could take an hour to accomplish.

Understandably, none of this was very popular with the astronauts. And while Mercury, Gemini and Apollo had been a men-only club, NASA now had female astronauts who would be flying on the new Space Shuttle, so any equipment also had to be gender-neutral. So when the Shuttle was being designed, careful thought was given to the problems of “going” in space.

The Space Shuttle had separate systems for liquid and solid waste. For peeing, the system was basically the same as that in Apollo–a tube that runs to the outside of the spacecraft. Both men and women pee into a funnel that fits onto the tube (each astronaut has his or her own personal peeing funnel), which is designed to be used both standing up or sitting down. The liquid is vented out into space. The males are cautioned to leave a little bit of distance to prevent “docking”.

The solid-waste system is much more complicated. The Space Shuttle’s toilet looks a lot like an ordinary toilet on Earth. But it functions completely differently. The first problem is that there is no gravity to hold you in place, so you have to strap yourself in. A set of foot restraints hold you to the floor, while a thigh bar (like the safety bar on a roller coaster) holds you to the seat and helps you get a good seal between your butt and the toilet rim. Since there is no gravity to make anything drop down and away, the inside of the toilet has a constant air stream that creates a partial vacuum, which usually pulls stuff down into the drain hole (astronauts are helpfully provided with a glove to use if things don’t quite work out right). The solid waste is pulled down into a chamber where it is desiccated and stored for removal upon landing. The air used for the vacuuming is filtered to remove germs and odors, then is recirculated with the rest of the air throughout the spaceship.

Because getting a good seal is so important (and also because the hole you’re aiming for is only four inches wide) astronauts have to undergo potty training before they can fly. At the astronaut center in Houston’s Johnson Space Center is the “Positional Trainer”. Here, the astronauts can practice their aim, with the help of a small video camera inside the toilet that helps them see what they are doing.

Space Shuttle toilet. California Science Center.

On the International Space Station, the toilet system is similar but adds a few functions. Because water is so precious, liquid waste and the water that is desiccated from the solid waste is collected in a special storage tank where it is filtered, purified, and returned back to the drinking water system. The remaining solid waste is compacted into a bag, and periodically it is loaded into a small container and dumped into space.

(By the way, if you get space-sick and have to throw up, barfing into the toilet is an absolute no-no. There are sealable “barf bags” helpfully located throughout the spaceship.)

So, what happens if you are outside the spacecraft and you gotta “go”? Most Space Shuttle and ISS missions involve “space walks” or “extravehicular activity”, in which space-suited astronauts perform various tasks while floating in space for several hours. The astronauts solve the potty problem with a simple solution–they wear diapers, known as “Maximum Absorbency Garments”, or MAGs. These can absorb and hold up to a quart of liquid and can be worn up to eight hours. They are also worn during takeoffs and landings, when the astronauts are strapped into their seats and the space toilet is not available.

The Japanese, meanwhile, are working on a “wearable toilet” that fits under the clothing like a diaper, uses a computerized motion-activated airflow to remove waste from the body, automatically washes the skin, and stores the waste for the rest of the flight. It may make the space toilet obsolete.

I wonder whether all that waste dumped into space doesn’t add to the space junk problem. How long does it take before it comes out of orbit? You surely don’t want to get hit in the face by a bagful while on a space walk…

They angle the dump so it enters atmosphere quickly, and burns up.