Thomas Edison is usually credited with inventing the electric light bulb. In reality, he did not. Contrary to the mythology, the light bulb was not the result of the insight of a single great genius, but a long collaborative effort by a number of people who were working independently of each other, made possible by a number of separate advances in technology.

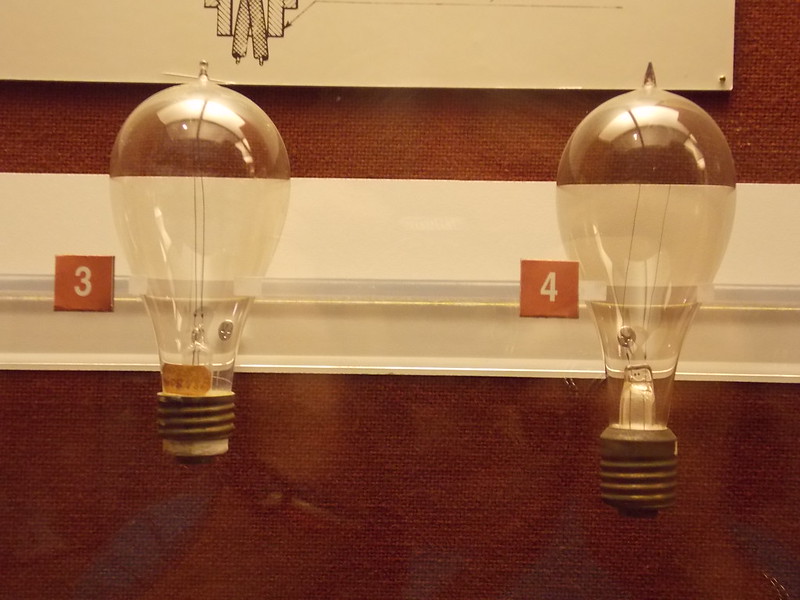

Edison light bulbs

In 1800, the Italian experimenter Alessandro Volta made the first “electric pile”, an alternating column of copper and zinc plates that was capable of producing a current of electricity. Today, we know it as a “battery”. Volta’s discovery probably did more than any other invention to transform the 19th century: the new source of energy came to dominate the world and “electrification” was the hallmark of technical progress—everything became powered by electricity, from industrial machinery to household toasters and washing machines.

Almost immediately, people began applying the principle of electric power to the problem of producing artificial light. As the 19th century began, the only practical source of indoors light were oil or kerosene lamps. These were smelly, smoky, and didn’t produce much illumination, and both whale oil and kerosene were expensive to obtain. It was quickly realized that the new energy from electricity could potentially be used to produce artificial light that was clean, bright, and cheap.

The first successful application of this new source of power came in England in 1806. Humphrey Davy passed an electric current through an air gap between two carbon rods, and as the spark jumped across the gap it produced a brilliant light. But Davy’s “arc lamp”, though sound in principle, had some practical difficulties. It used an enormous amount of electrical power, and the crude batteries and generators of the time were not capable of keeping up. It was also tremendously bright—like a modern arc-welder—and was not suited for everyday use.

Over the decades, as electric generators became powerful enough to supply massive currents and carbon electrodes of the necessary purity became available, Davy’s arc lamp was developed into powerful sources of illumination such as theater spotlights, lighthouse lamps, and military searchlights. But for use in artificially lighting homes at night, it was apparent that something different was needed.

One of the properties of electrical conductors found by researchers was “resistance”. The higher the electrical resistance, the harder it was for electrons to pass through; the higher the electrical resistance of a material, the higher its temperature became when a current was passed through it; and, experimenters quickly realized, at very high temperatures many materials glowed and gave off light. This effect was “incandescence”, and it quickly became the most promising method of producing artificial light with electricity.

As Davy had already found, carbon was a good material for this, but it was too powerful for most uses: what was needed was some other material that could be impregnated with carbon to “subdivide” the light, not so blindingly strong as a carbon arc, but still bright enough to be useful. In both Europe and the United States, a large number of researchers took up the problem, experimenting with a bewildering variety of materials to find the best “filament” that could produce a steady light when electrified. Most of them, alas, either burned up or melted. For the next three decades the problem remained unsolved.

Then a technological advance allowed a new approach. For many years now, science knew that the atmosphere was made up of a mixture of different gases, and that pumps could be used to remove the air from heavy glass jars to produce a vacuum. By the 1830s, improved glass technology was now able to contain these vacuums inside light thin glass containers—the “bulb”.

In the next century, this would lead to the “vacuum tube” which would revolutionize radio communications and computer technology, but in the first half of the 19th century, the “vacuum bulb” offered a way forward for those who were seeking a practical method of producing artificial light. The biggest difficulty in producing an incandescent filament was the tendency for materials to burn up when they were heated by an electric current. Now, these bulbs offered a solution: fire and combustion could only take place in the presence of oxygen, and in a vacuum bulb with the air removed, there was no oxygen. Materials could now be heated to high temperatures without burning up.

The idea caught on almost everywhere. In 1840, British researcher Warren de la Rue began using filaments made from platinum metal, which had a very high melting point, and coated them with carbon to give a high resistance and produce light. And when he placed this apparatus inside a vacuum bulb, it worked. In 1841, another British researcher named Frederick DeMoleyns independently duplicated la Rue’s discovery. The platinum allowed the filament to survive long periods of current which could be switched on and off, and the carbon gave a reasonable amount of light.

Others followed. In 1845, an American named JW Starr patented his own version, based on a thin carbon bar as a filament. An Englishman named Joseph Swan followed in 1850: after experimenting with a wide variety of materials, Swan made his filament from a strand of paper coated with carbon.

But practical problems remained. Platinum was rare and expensive, and only Swan’s paper filament was able to bring the cost of a light bulb down to something that would make it widely available. But Swan, like all the others, also faced the fact that the technology of the time was simply not able to produce a very good vacuum, and his paper filament, like the others, was still being oxidized and burned out after a while. And all of the various filaments being used had the undesired quality of emitting fumes which eventually coated the inside of the light bulb and reduced its effectiveness.

In 1874, a pair of Canadians named Henry Woodward and Matthew Evans tried a different approach: if they could not effectively remove all the air from inside the bulb, perhaps they could instead replace the oxygen with something else. So Woodward and Evans filled their glass bulbs with inert nitrogen. It worked and prevented the filament from being oxidized, but it still presented many of the same problems being faced by the others.

In 1878, a new and formidable investigator entered the field. Thomas Edison was already famous for inventing the phonograph, and his research lab in New Jersey was one of the best-equipped and most well-funded in the world. He also had the advantage of entering the field just as a solution to all the old problems was appearing: in the 1870s newer improved pump technology meant that now tinkerers could reliably produce very good vacuums inside their glass bulbs, and the problem of oxidation was no more. With his virtually unlimited research funds, Edison’s lab was able to test a wide variety of materials as possible filaments, and by 1880 found what seemed to be the best option—a thin piece of bamboo coated with carbon. Eventually Edison was able to get his bamboo filament to burn for over one thousand hours. The Edison Company filed patents on its electric light bulbs in October 1878 and November 1879.

Meanwhile, in England, Joseph Swan, who had patented his own paper filament light bulbs back in 1850, was also experimenting with better vacuums, and was also using carbon-coated cotton string as the basis for a new filament. He patented his new design in 1878, demonstrated a working model at a lecture in Newcastle in February 1879, and opened his own electric light company in 1880.

When the Edison Company began manufacturing and selling light bulbs in 1880, the two companies clashed, and Edison sued Swan for patent infringement. Despite the Edison Company’s massive advantage in legal resources, however, Swan had a strong counter-case: he (and others) had been making electric light bulbs for 20 years now, and he had demonstrated his design publicly before Edison had. Unable to prove in court that he had invented the light bulb, Edison instead resorted to the superior economic strength of his large company and simply bought out Swan’s patents and took him in as a partner. The Edison-Swan United Company quickly became the largest manufacturer of light bulbs in the world. Over the next few years, Edison purchased the patents of nearly all of his potential competitors, merging them all into the General Electric Company. It would become one of the largest corporations in the world.

Edison’s real contribution to the spread of artificial lighting, however, came from the opposite end of the process. All of the various early researchers had sought to perfect the light bulb as a method of utilizing electricity to produce illumination. But only the Edison Company, with its huge research lab and massive economic power, had the resources to tackle the biggest problem of all—how to effectively generate electricity at large scale and then distribute it efficiently to individual households where it could power not only light bulbs but electric appliances of every sort. The Edison Electric Illuminating Company of New York was set up, with lavish funding from robber baron banker JP Morgan, specifically to solve this problem, and by September 1882 the fashionable Perl Street neighborhood in Manhattan was being served by an Edison generating station and a network of power lines that carried electricity to each home, and would soon be turned to running everything from street lamps to trolley cars. The Electric Age had begun.

Today, a display of Edison light bulbs, along with some of his early competitors, is on exhibit at the Smithsonian Museum of American History in Washington DC.

RESEARCH IS THE REWARD; WordPress.com…