In 1848, all of Europe faced a series of rebellions and revolutions. In what some referred to as “The Springtime of the People”, pro-democracy and pro-reform demonstrations broke out in every capitol of Europe. The “Year of Revolution” toppled regimes, altered the political history of Europe, and inspired a German economist named Karl Marx to write a pamphlet entitled “The Communist Manifesto”.

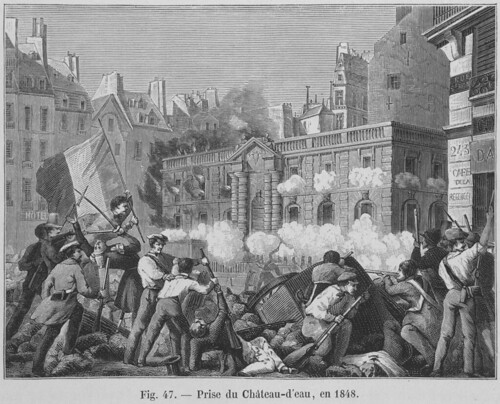

The 1848 Revolution in Paris photo from Wiki Commons

After the French Revolution of 1789 overthrew the most powerful monarchy in the world and declared a democratic Republic, the idea of democracy was planted all across Europe. The result was 50 years of civil war and internal repression, as monarchies sought to hold back the tide of democratic ideology and maintain their positions of power, and ethnic and national minorities fought for independence and citizens fought for a democratic government. In Italy, Austria, Hungary, and the principalities that made up the region of Germany, royal houses formed secret police forces and stationed troops in the capitol to silence dissent and crush pro-democracy demonstrations. In England, where royal power had already been subject to limits by a Parliament, a mass movement known as the “Chartists” used written petitions with six million signatures to demand that the Parliament be made democratic, with freely-elected members under universal suffrage (without property qualifications for voting). In France itself, Napoleon Bonaparte destroyed the Republic and declared himself Emperor, and after his defeat the French monarchy had been re-established under King Louis-Philippe.

There was also another force at work. Led by England, the European economy was changing. For centuries, Europe had been an agricultural society where large land-owners held the economic and political power. But now the world was being changed by industrialization, in which huge factories were mass-producing a level of products that had been unthinkable in previous times. These factories were owned by a rapidly-rising middle class, whose wealth soon led to political influence and conflict with the traditional land-owners and royal nobility. The factories also produced an entirely new social class–the industrial workers, who labored long hours in the factories, in horribly unsafe conditions for meager pay, and who lived in poverty in crowded urban tenements, voiceless and powerless. The aspirations of the working class were expressed in the ideologies of socialism and communism, which envisioned not only political democracy, but economic democracy as well. It was a social situation that was ripe for an explosion. And the explosion happened early in 1848.

Sparks had already appeared. In January 1848, demonstrations broke out in Milan, then a part of the Austrian Empire, after another increase in taxes was announced, and 61 demonstrators were killed. And later that month, pro-democracy protests were held in Sicily.

In France, the pro-democracy movement had been driven underground by police repression, and now took the form of “banquets”, large dinner parties held by political idealists which featured speeches calling for democracy and the restoration of the Republic. In February 1848, King Louis-Philippe outlawed “banquets” along with all other political gatherings. In response, Parisians took to the streets, and 40 protesters were shot by the King’s troops. That fueled even larger demonstrations, and events happened quickly. Mobs of demonstrators invaded the Chamber of Deputies. King Louis-Philippe abdicated and fled to England, leaving his nine-year old nephew as the titular King of France. The revolutionaries seized the government, and declared the Second Republic on February 24. In March, the revolutionary government opened a program of public-works projects to provide jobs for the working class poor, and announced free elections for April.

Within weeks, news of the victory of the French democracy movement shot across Europe and unleashed a wave of rebellions. In Germany, rebellions broke out in Munich, Cologne, Mannheim and Berlin, local princes and the king were removed in Bavaria, and in Prussia King Wilhelm was forced to produce a new constitution and promise democratic elections for a Constituent Assembly. In Vienna, the Hapsburg Emperor’s Prime Minister fled to England. In Italy, uprisings in Milan and Venice led to the withdrawal of Austrian troops and independence. In Budapest, street demonstrations forced the Austrian Emperor to grant autonomy to Hungary: in Prague, revolts demanded independence for a Czech nation. Independence movements also took to the streets in Poland, Bessarabia, and Romania. In England, where Chartist demonstrations broke out, the Queen was moved to the Isle of Wight for her own safety, and one thousand troops under the Duke of Wellington were dispatched to guard London.

When the French elections were held in April, the radical socialists and communists found themselves in a minority. As a result, when the Republic announced that it would end the public-works project, the working class radicals, unable to influence the Assembly, took to the streets instead. In the rebellion that became known as “The June Days”, barricades and red flags went up all over Paris, the Army went in with cannons and bayonets, and 1500 rebels were killed in the fighting.

Once again, a victory in Paris set the tone for events in Europe, but this time in the opposite direction. Now, the royalist reactionaries had the momentum, and government troops were sent in to crush nationalist pro-democracy rebellions in nearly every major city in Europe, including Prague, Vienna, Berlin, Milan, and Budapest. By October 1848, the “Year of Revolution” was over, and the European monarchies were firmly back in control. In the December French elections, Louis Napoleon, the nephew of Bonaparte, won, and promptly disbanded the Second Republic and declared himself Emperor.

In the end, none of the 1848 Revolutions achieved their goals, the monarchies of Europe emerged more powerful than before, and a wave of reaction and repression swept the continent, arresting thousands and setting back the democracy movement for decades. It would not be until the cataclysm of World War One reduced Europe to a smoking blood-stained ruin that the last defeated royal empires would finally fall, and parliamentary democracy would establish itself in every major country.

The 1848 Revolutions would have one other long-term effect. In 1847, a group of German exiles living in London had formed a group to agitate for democracy and socialism. Originally called the “League of the Just”, they changed their name to “The Communist League”. That July, they appointed a German exile named Karl Mark and his partner Friedrich Engels to draft a platform for the group. When the February 1848 revolt broke out in France, Marx left London for Paris, and the following month published The Communist Manifesto, which spelled out his ideas about class struggle, historical materialism, and the downfall of capitalism and the rise of communism. When the reaction set in and the Republic began arresting radicals, Marx tried to leave for Switzerland but was denied entry, and instead returned to London. Marx’s pamphlet was little noticed at the time and played no role in the 1848 rebellions, but by the time of the next major social upheaval in France, the 1870 Paris Commune, Marx’s Manifesto had fueled one of the most powerful political movements in the world.