The 1970 Soviet lunar probe Lunokhod was overshadowed by the American Apollo moon landings, but it was a significant technical achievement in space exploration.

By 1961 the Soviet Union was far ahead in the Space Race. The USSR had successfully launched the first satellite and had placed the first human into space. The United States was still struggling with its own space program, but now set itself the ambitious goal of putting a man on the Moon, hoping to leap ahead of the Russians.

The Soviets, however, had more challenging aims: they were already looking at the long-term goal of establishing an inhabited base on the Moon and a permanently manned space station. Part of this strategy involved sending humans to the Moon, using an enormous rocket that would be dubbed the N-1, and a long-duration variant of the Soyuz spacecraft known as “Zond”. But there would also be a systematic effort to explore the lunar surface using unmanned remotely-operated probes. These would be known as “Lunokhod” (Russian for “moon vehicle”). In the end, the massive N-1 Moon rocket would turn out to be a failure, and the Soviets abandoned the goal of landing a human crew on the Moon and focused on a space station instead. But the Lunokhod program would go on to success.

The initial design work was done in 1963 by the Lavochkin aircraft bureau, which had produced several models of fighter planes during the Second World War and had gone on to design the Soviet Venera probe to Venus and several of the Luna probes to the Moon. Most of the final design and testing for the lunar rover was then done at the Transmash Bureau in Leningrad, which had successfully produced a number of different tanks and armored vehicles for the USSR. Alexander Kemurdzian, an engineer who worked largely on designs for air-cushioned hovercraft, was placed in charge of the project. The idea was to produce a vehicle that could be landed on the Moon and then move around under its own power to conduct observations and send back data, controlled and directed by a team of engineers back on Earth.

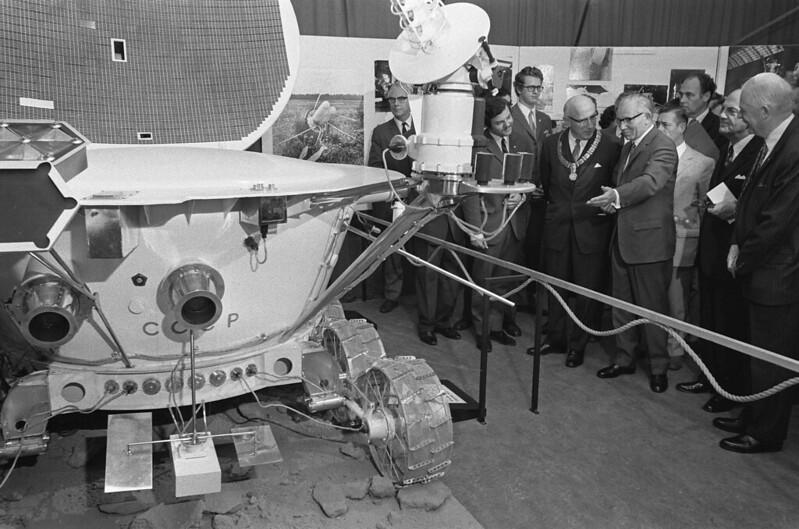

It was a daunting task, and would require some significant advances in the field of robotics, computers and electronics—all of which were still in their infancy. There were severe size and weight restrictions, and everything had to work in a vacuum at just one-sixth of Earth’s gravity (and this presented difficult issues with some components like lubricants). There was also the problem of how to steer and control the rover in real time and how to power all of the various apparatus that would be necessary. The Lunokhod was intended to carry two television cameras, four still cameras, an X-ray telescope, radiation detectors, a laser reflector, a device to measure distance traveled, and some other instruments.

It was decided to power the Lunokhod with a set of batteries which would be recharged as needed by a solar panel. The panel would be stored inside the vehicle and open up to the sun when the battery got low. During the lunar night (which, like the lunar day, lasted about two Earth weeks), the electronics inside the probe would be kept warm by a small heater that was powered by radioactive decay from a plug of polonium-210. In total, the vehicle produced about 300 watts of electricity—just a couple of light bulbs’ worth.

To test out various potential designs, the Soviets built a “lunar drome” to mimic the conditions they expected to meet on the Moon, but this was largely guesswork since nobody really knew yet what the lunar surface was like. There was debate over whether the rover should have wheels like a car or tracks like a tank (and there were even some early designs that used a “walking” motion to propel the probe over the surface). It was ultimately decided to have eight mesh wheels that operated independently, which would minimize the chances of having the vehicle be disabled by a malfunction or get stuck on rocks or the lunar soil. The “Lunadrom” was then used to train the operators (recruited from the Soviet Army) who would be remotely controlling and driving the probe. Further testing was also done at a volcanic landscape in Kazakhstan.

Four complete Lunokhods were finished by 1968. They were roughly the size of a small car, measuring about 7.5 feet long and 5 feet wide, and weighing a bit over 1600 pounds.

To deliver the Lunokhod to the lunar surface, the Soviets were using much of the same hardware that had originally been intended for a manned landing. The rover would be fitted atop a “Luna” lander, which had been designed to carry cosmonauts to the surface from “Zond”. The Luna/Lunokhod combination would be launched from Earth atop the new Proton-K rocket and would travel to the Moon. Luna would be placed into lunar orbit, and would descend to the surface; Lunokhod would then be driven down an extendable ramp.

By February 1969, everything was ready. The Russians had already launched a number of Luna probes to the Moon with instrument packages to examine the conditions there. The American program, meanwhile, would soon be making an attempt at a manned lunar landing, and the Soviets were hoping to steal some of Apollo’s thunder with a successful lunar rover. But they were to be disappointed: upon launch, the Proton rocket malfunctioned and exploded, destroying the first Lunokhod. The Russians watched in frustration as the American astronauts landed on the Moon in July 1969.

By November 1970 the Soviets were ready to try again, and this time everything worked as planned. The Luna 17 craft, with Lunokhod aboard, soft-landed on the Moon on November 17 at the Sea of Rains, and the vehicle rolled onto the lunar surface 2.5 hours later. Originally planned for a mission of three days, the rover continued to operate successfully for 11 months, traveling about 6.5 miles across the surface and sending back photos, TV video and data. It was the first remote-controlled rover to land on another astronomical body.

Lunokhod 2, with improved scientific instruments, landed on the Moon in January 1973 and explored for four months, traveling 23 miles before its power ran out. The last rover, Lunokhod 3, was scheduled for launch in 1977, but by this time the Soviet space program had moved on to other priorities and the mission was canceled. The Lunokhod 3 is now on display at the Lavochkin Museum near Moscow.

It would be another two decades before anyone would launch another rover, when the United States landed the Pathfinder on Mars.

But the Lunokhod story wasn’t quite over yet …

In April 1986, the nuclear power plant at Chernobyl exploded in the worst nuclear accident in history. To help clear the intensely radioactive debris from the area, the Soviets hastily designed and built a small unmanned vehicle that could bulldoze bits of the reactor from the roof of the destroyed building without exposing anyone to the lethal radiation. And this device was produced and remotely operated by the same team of engineers who had landed the Lunokhod on the Moon, fifteen years before.