The most famous Japanese aircraft of the Pacific War was the Mitsubishi A6M Zero. But the Zero was only used by the Imperial Navy, mostly as a carrier-based fighter. The Imperial Japanese Army had its own series of fighter planes during WW2, which were ground-based. Today, they have been almost entirely forgotten.

After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the Empire of Japan moved away from its feudal isolation, which had lasted 200 years, and embraced European technology and culture in an attempt to catch up to the rest of the world. By 1905, the once-backward nation was strong enough to take on the Russians in the Russo-Japanese War and beat them soundly.

One area that the Japanese military was particularly interested in was aviation. Even before the First World War, Japan had purchased a number of French and British biplanes and begun producing its own copies. In the naval sphere, Japan was one of the first countries to invest heavily in aircraft carriers.

By the time Japan invaded China in 1937, the Imperial Army had over 1,000 combat aircraft. And while the Chinese were provided with older American- and Russian-built fighters, the modern Japanese Army fighters were superior.

At the time of the Japanese invasion, the standard Imperial Army fighter was the Nakajima Ki-27, known to Allied intelligence as “Nate”. (The Americans and British gave codenames to Japanese aircraft made up of boy’s names for fighters and girl’s names for bombers.) In many ways, the Nate was Japan’s first modern fighter, replacing older canvas-covered Ki-10 biplanes with an all-metal monowing. Originally, Nakajima had offered a design with a liquid-cooled inline engine and retractable landing gear, but the Army thought this would be too prone to failure, and ordered a radial engine design with fixed landing gear. Adopted in 1937, the Nate had a top speed of 275mph and was armed with two .30-caliber machine guns.

In combat over China, the Ki-27 performed well against the Russian-made I-15 biplanes which made up of the bulk of the Chinese forces. During the Khalkhin Gol Incident of 1939, Japanese Army Nates faced the Soviet I-16 monoplane and did pretty well, but they proved to be poor performers against the newer American P-40s being provided to China in 1940.

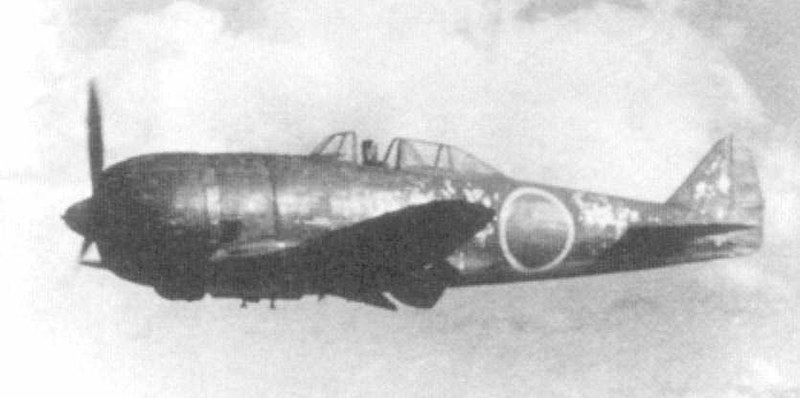

As a result, the Army called for a new and better design, resulting in the Nakajima Ki-43 “Oscar”. Similar to the Imperial Navy’s Zero, which was also being developed at about the same time, the Oscar was a single-engine monoplane with retractable landing gear and an 1150-horsepower engine with a speed of over 300mph. It was armed with two .50-caliber machine guns and could carry 500 pounds of bombs. Plans to fit the fighter with 20mm cannons were never successful, as the airframe proved to be too lightly constructed to withstand the recoil.

Introduced in April 1941, the Oscar quickly became a favorite with pilots. It was fast and maneuverable. Like the more famous Zero, the Oscar would remain in production all the way through the war, and although it became more and more outclassed by newer American fighters, in the end the Ki-43 would shoot down more Allied aircraft than any other Japanese plane in the war.

The Imperial Army was also impressed by the Messerschmitt Me-110 twin-engine two-seat “heavy fighter” which was being produced by Nazi Germany as a long-range bomber escort, and in 1937 began work on its own version, the Kawasaki Ki-45. Early versions used the Ha-20 engine which, at just 800 hp, was underpowered. In October 1940 the engines were switched to the more powerful 1080 hp Ha-102, and the Ki-45 was adopted into Army service in February 1942. It was given the Allied codename “Nick”.

But, like its German counterpart, the twin-engine Nick proved to be a failure in combat. It was too lumbering to stand up against far more agile single-engine fighters, and in bomber raids over China and Southeast Asia it was outclassed by American P-40s and British Hurricanes. The Imperial Army began using Oscars as escort fighters and assigned the Nick to ground-attack and anti-shipping instead. Later, armed with a 37mm cannon, it became a successful bomber interceptor, capable of shooting down even the formidable B-17. But when the Americans began their air raids on Japan using B-29s, these proved to be able to fly too high for the Nicks to reach. The Japanese frantically tried to improve the Ki-45 into a high-altitude night-fighter, but Japanese radar was never that good, and although it saw some success once the Americans switched their B-29s to low-altitude incendiary raids, by the end of the war the Nick was being used almost exclusively for suicide kamikaze attacks on shipping.

Meanwhile, as the war began going badly for Japan, the Army was scrambling for a fast high-altitude interceptor with more firepower than the Oscar, which could shoot down American bombers. The first of these was the Nakajima Ki-44, heavily armed with two .50-caliber machine guns and two 20mm cannons (some later versions had four 20mm cannons or two 40mm).

Fast and with a high rate of climb, the Ki-44 (given the codename “Tojo” by the Allies when it was introduced in early 1942) proved itself capable of intercepting even the B-29. But only a little over a thousand of them were produced during the war, and by 1944 the Tojo was being replaced by the newer Ki-84 Frank.

When the German Luftwaffe offered to let Japan build licensed copies of their Messerschmitt Me-109 fighter, the Japanese turned them down, ultimately preferring to focus instead on their own Oscar and Zero designs. But the Imperial Army liked the water-cooled inline Daimler-Benz engine used by the Germans, and agreed to manufacture a licensed copy for use in one of their own aircraft. Introduced in early 1942 and first seen by the Allies during the Doolittle raid, the Kawasaki Ki-61 was mistaken by the Allies as being a copy of the German Me-109 or the similar Italian Macchi C.202, and was given the codename “Tony”.

The Tony quickly proved to be a flawed design, however, and although it could defeat the older American fighters like the P-39 and P-40, it was no match for later models like the F4U and P-51. The Japanese were never able to make a reliable version of the Daimler-Benz engine, which crippled the fighter. Towards the end of the war the Tony’s airframe was re-fitted with a more reliable radial engine to produce the experimental Ki-100, which could match the latest American fighters, but this came too late. By the end of 1944 Ki-61s were being stripped of their guns and armor so they could be sent on one-way missions against high-altitude B-29s with the intention of ramming them.

In 1943, Japan introduced what is considered to be the best Imperial Army fighter of the war, the Nakajima Ki-84. By this time, Japanese fighters were heavily outclassed by newer American models, and the Nakajima company set out to make improvements. The new design included defensive armor for the pilot and self-sealing gas tanks, a more powerful engine, and an improved armament with two 20mm and two 30mm cannons. It was given the Allied codename “Frank”.

It was not enough. Although the 2000 hp Ha-45 engine was capable of pushing the Frank to 380mph, Allied fighters of the time were already exceeding 400mph. Throughout the entire war, Japan always had trouble producing a high-powered aircraft engine or the high-octane fuel necessary to run it, and these efforts would be hampered by constant B-29 bombing raids on factories and refineries. But the biggest problem with the Frank was that there were simply not enough trained and experienced pilots to fly it. The grinding years of war had killed or incapacitated most of Japan’s fighter pilots, and she was incapable of training a sufficient number to replace them. By the end of the war, the Ki-84 was carrying barely-trained pilots on one-way suicide missions.

Crap. Wrong link was still in clipboard, and the new one didn’t properly. This is the correct one:

This is interesting. I didn’t know that Japan had such a collection of aircraft!

The Japanese Army and Navy mostly didn’t talk nice to each other. And they had entirely different views of what they wanted: the Navy wanted long-range reach, while the Army wanted short-range tactical support.

Just the other day I happened across an interesting, and thoroughly comprehensive, account of the surviving documents concerning the Army’s evaluations of the BF109E. This is kind of an avgeek deep dive, but it does illuminate the differences between the design & tactical philosophies of not only the Germans and Japanese, but the Imperial Army and Navy.

In the early part of the war, the US pilots were constantly reporting the Tony fighters as “Me-109s”.

Speaking of the Tony and the dwindling Japanese supply of experienced pilots:

I recall from childhood reading an account in one of those rah-rah glamorized fighter pilot books common in 1960’s libraries, about “The Flying Undertaker” William Shomo, who with his wingman shot down 11 hapless Tonys in a single mission.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_A._Shomo