When the US Army bought its first airplane, it wasn’t really sure what to do with it. But within just a few years, the Signal Corps was experimenting with different ways to utilize air platforms.

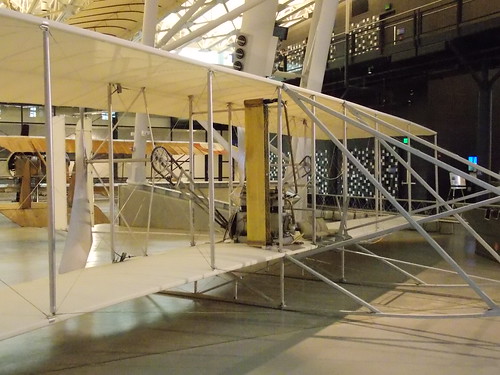

Replica 1909 Military Flyer in Smithsonian Udvar-Hazy

With the success of the Flyer III, the Wrights decided that they were ready to begin offering a commercial version of their flying machines. And naturally they presumed that their best customer would be the US Army.

In January 1905, the brothers contacted their local Congressman, Robert Nevin, who agreed to submit a proposal from them to the US Secretary of War, William Howard Taft, describing the capabilities of their aircraft and offering it for the Army’s consideration at a proposed price of $25,000 per machine. Their Flyer, they noted, had now made over 150 flights, in straight paths and circles and in various wind conditions, and would, they thought, be of great use to the military in “scouting and carrying messages in time of war”. Nevin submitted the letter to the War Department, who in turn passed it to the Army Ordnance Board.

In response, however, the Wrights received the standard form letter that was sent to all of the dozens of requests that the Army received asking for funding to build a flying machine, declining to provide any money until a particular design had reached “practical operation”. Puzzled, Wilbur wrote again, explaining that they were not asking for money to build a flying machine—they already had one, and were offering it for sale. In reply, they once again received another form letter.

It’s not clear today whether this snub was due to reluctance on the Army’s part to become involved again with a “flying machine” so soon after Langley’s spectacular and expensive failure, or to bureaucratic inertia and bungling, or simply to a disbelief that the Wright’s machine could actually do what they said it could do. In any case, the brothers, exasperated, in essence decided that the US had its chance and had blown it, and now approached the European countries instead. By 1906, serious talks had begun with the French, British, and Germans.

But when the US Government got wind of this, however, it decided that it didn’t want to miss the boat, and negotiations soon began. In December 1907, the Army Signal Corps formally issued Specification Number 486, a request for proposals for a “heavier-than-air flying machine”. The Army specified that the machine had to be capable of carrying two people (a pilot and observer) with a combined weight of 350 pounds, have a flight range of at least 125 miles and a speed of 40mph for at least one hour, that it be able to take off and land from unprepared ground, and that it could be disassembled for transport in a standard Army wagon. The purchase price was set at $25,000 per plane, with a bonus of 10% for every average mile per hour over 40 and a 10% penalty for every mile per hour under.

Although the War Department received a total of 41 proposals, only one of them had actually built and flown a flying machine, and the Wrights were the only ones to bring an aircraft to Fort Meyers VA in 1908 for evaluation. Basically a modified Flyer III with a bigger engine, the “Military Flyer” met all the Army’s specifications, and by exceeding the 40mph requirement by 2mph, it earned the Wrights a $5,000 bonus.

But during the test flights, tragedy struck: one of the propeller blades broke and the Flyer plunged to the ground. Orville Wright, who was piloting the craft, suffered a broken hip. His observer/passenger, Army Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge, was killed. The Wrights took the engine from the crashed aircraft and built a new frame, with a modified rudder and some changes to the wire rigging. Testing resumed in June 1909. At one point, William H Taft, now the President of the US, went to observe some of the flights.

On August 2, 1909, the Army Signal Corps formally accepted delivery of “Aeroplane Number 1”. The Wrights were retained under contract to train three Army volunteers as pilots: Lieutenants Benjamin Foulois, Frank Lahm, and Frederic Humphries. In February 1910, Aeroplane Number 1 and its new pilots arrived at Fort Sam Houston in Texas. It remained the Army’s only aircraft for almost another year, and was crashed and repaired several times.

Other nations soon joined in the field of military aeronautics. In Europe, armies began purchasing planes designed by Voisin, Farman, and Blériot, who were making important technical advances. In Mexico, Alberto Braniff was flying a Voisin biplane which he had brought back from France. In the US, the Signal Corps soon obtained a number of Wright Model B aeroplanes and began experimenting with light machine guns: meanwhile, pilots in the Balkans War of 1912 were dropping grenades out of airplanes. One of the first conflicts in which both sides had military aircraft was the Mexican Revolution, when guerrillas under Pancho Villa flew Martin and Curtiss aeroplanes that they had captured from the Madero Government. In early 1914, one of the Mexican biplanes dropped a number of small bombs onto a rival gunship, the first known air attack on a ship at sea. Despite some ill-informed resistance (one US congressman famously remarked, “What’s all this talk about aeroplanes—I thought the Army already has one?”), the airplane was finding its place as a weapon of war.

By 1911, the US Signal Corp’s Aeroplane Number 1 was retired from active service. In March 1911 it was donated to the Smithsonian. Today, the original 1909 Military Flyer is on display at the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum. There is also a reproduction on display at the Udvar-Hazy Center, and another replica is exhibited at the US Air Force Museum in Dayton OH.