When the Wright Brothers took off at Kittyhawk in 1903, people had already been flying for over a century. In fact, the first manned flights were launched in front of huge crowds in Paris, just a few years before the French Revolution. But they did not happen in airplanes.

For thousands of years, the Chinese had been making “Konming Lanterns”. These were paper bags attached to a small wooden frame which held a candle. The warm air from the candle gathered in the bag, causing the lantern to float off into the sky. Although used primarily for religious festivals, they were also used on the battlefield as signalling devices. When a Brazilian priest living in Lisbon, Father Bartolomeu de Gusmão, used the heat from a candle to float a small paper bag at the court of King John V in 1709, he had probably gotten the idea from descriptions given to him by fellow Portuguese clergymen who had been to China.

The ancient Chinese did have the technological capability of constructing a larger version of the Konming Lantern–big enough to carry a human aloft–but there is no indication that they ever tried it. Renaissance Europe almost certainly knew of the Chinese lanterns, but never did anything with the idea.

In 1782, a pair of brothers in Paris, Jacques-Etienne and Joseph-Michael Montgolfier, began their own experiments. They owned a paper-making shop, and one day one of the brothers had happened to see a paper bag, filled with hot air from the machinery, float off the floor. With bigger bags, they found that they could lift objects into the air–and the idea came that if they made their balon bag large enough, they could lift a person into the air. They could fly.

Using taffeta cloth that was glued over with strips of paper, the brothers had a material that was sufficiently light, strong and airtight to make large bags, which they heated up with a straw-fueled fire built underneath. Not realizing that it was the less-dense hot air that was producing the buoyancy needed for flight, the brothers thought they had found a new type of gas that was lighter than air, which they referred to, immodestly, as “Montgolfier Gas”.

Confident in their new gadget, the Montgolfiers announced that they would make a public flight of their balloon on June 4, 1783. The 33-foot bag was inflated by hot air from a fire on the ground at the Anonnay Marketplace and was then released. Unmanned and unguided, the balloon rose steadily, climbing quickly to an estimated 5-6000 feet, and floated off on the wind. With no fire on board, the air inside the bag began to cool, causing the balloon to steadily descend. It stayed aloft for 10 minutes before settling back on the ground, covering a distance of over a mile.

The “hot-air balloon” had been born. But it already had competition.

In 1766, almost 20 years before the Montgolfier brothers thought they had discovered a new gas, the English chemist Henry Cavendish had in fact discovered the gaseous element hydrogen and studied its properties. One immediately obvious characteristic was that hydrogen gas was lighter than air, and floated upwards. Years later, an experimenter in Paris named Jacques-Alexandre Charles came upon Cavendish’s work and immediately grasped what this meant: if he could fill a large gas-tight bag with hydrogen, it could produce enough lifting power to carry a human.

Making enough hydrogen gas for such a device was the easy part. By mixing iron and sulphuric acid, he produced a chemical reaction that released pure hydrogen gas. The hard part was constructing a large durable bag that was sufficiently gas-tight to be inflated. After a series of experiments, Charles found a workable method: he sewed pieces of silk to form a bag and coated this with a solution of rubber dissolved in turpentine, which sealed all the seams and prevented the hydrogen from passing through the cloth.

By August 1783, Charles was ready for a demonstration flight of his gas balloon. The bag he built was about 12 feet wide, and had lift sufficient to carry about 20 pounds. On August 27, after filling his balon with hydrogen gas in front of a large crowd of Parisians at the Champ du Mars, he released it. The American ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin, was among the spectators who watched as the balloon lifted into the sky, reaching a height of several hundred feet and drifting northwards with the wind. As people on horseback followed along, it flew for 45 minutes before landing in the little village of Gonesse. The experiment then ended ignominiously, as the terrified peasants of Gonesse, thinking that any large thing that had drifted silently down from the sky must be demonic, attacked the balloon and tore it apart with their pitchforks.

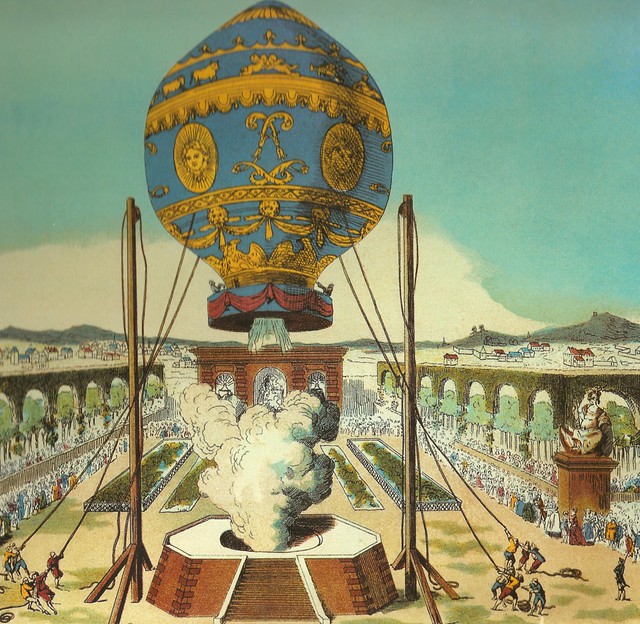

The next logical step was a manned flight, and both Charles and the Montgolfiers made their plans. The brothers were ready first. Louis XVI, the King of France, had heard about the earlier flights and was interested, and invited them to make their next flight from the grounds at the Royal Palace. Their new balloon, made with the help of local wallpaper manufacturer Jean-Baptiste Reveillon, was 30 feet in diameter and was decorated with zodiacal signs and suns, in honor of the French “Sun Kings”.

Since nobody knew anything at all about how the human body would react to the cold thin air at high altitudes, it was decided that a test flight would be made first. King Louis helpfully offered to provide a couple of condemnded criminals as test subjects to be sent aloft, but the Montgolfier brothers decided on a more scientific selection of pasengers: they would send a sheep, a duck, and a rooster. The sheep, they concluded, was a good stand-in for a human, being about the same in size and lung capacity. The duck and rooster would be the “controls” in the experiment; since ducks often fly at high altitude it was expected that the balloon ride would not effect it at all, and the rooster, being a bird that did not fly to high altitudes, provided an additional check on the flight’s effects. To hold the passengers, a woven wicker basket was attached at the bottom, hanging below the balloon.

All was ready within a month, and on September 19, 1783, the first air passengers lifted off. Eight minutes later, they were back on the ground, and all were happy and healthy. It was the human’s turn now.

Once again, the Montgolfiers politely turned down Louis’s offer of some prisoners as human guinea pigs, and instead selected a Paris professor named Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and a French military officer named Francois Laurent Marquis d’Arlanders as the first air travelers. The balloon, now named the Aerostat Reveillon, was modified: the bag was almost 50 feet wide, and the wicker basket was replaced with a circular wooden platform where the passengers stood. To give a longer flight, they would carry a fire along with them in an iron tray slung in the center of the platform. The balloon bag was fireproofed by coating it with alum. In October a final test was made by raising the tethered balloon to a height of several hundred feet with Pilâtre de Rozier aboard, and when he showed no ill effects from the altitude, the flight was ready.

On November 21, 1783, the Aerostat Reveillon lifted off from the Bois de Boulogne, in front of a cheering crowd that included King Louis XVI, his wife Queen Marie Antoinette, and US ambassador Benjamin Franklin. Franklin later wrote, “We observed it lift off in the most majestic manner. When it reached around 250 feet in altitude, the intrepid voyagers lowered their hats to salute the spectators. We could not help feeling a certain mixture of awe and admiration.” Reaching an altitude of around 500 feet, the balloon covered a little over five miles in 25 minutes. The fire had enough straw fuel aboard for at least another hour, however the pair became concerned when sparks began smoldering on the alum-coated paper envelope, and decided to land. But for the first time in history, humans had flown. The “Montgolfier Balloon” became a sensation. In one of the first examples of “merchandising”, commemorative dinnerware was produced with depictions of the flight; clocks were made in the shape of a balloon. The brothers became the most famous people in Paris. By January 1874, just two months later, larger versions of their hot-air balloon were carrying groups of up to seven people and reaching altitudes over 3000 feet.

But the future of flight did not belong to them. When Jacques-Alexandre Charles finally got his new hydrogen gas balloon ready on December 1, 1783, ten days after the Montgolfier balloon’s flight, he conclusively demonstrated that his was the superior flying apparatus. The hydrogen balloon did not need a fire or fuel, and its gas bag could carry it higher and further. The first manned flight of a hydrogen balloon took off from the Royal Garden at the Tuileries in front of a crowd of 400,000 Parisians, including the King, Queen, and much of the French nobility, and, once again, Benjamin Franklin. Also on hand to watch was Joseph-Michael Montgolfier. It was piloted by Charles and one of his partners, Nicolas-Louis Robert. The gas balloon reached an altitude of 1800 feet (Charles was carrying a barometer and a thermometer with him to take measurements), and flew over two hours before setting down at dusk, 25 miles away.

About a year later, in January 1785, the first successful balloon flight was made across the English Channel. It was a hydrogen gas balloon. When lightweight gasoline engines became available in the 1890’s, steerable “airships”, which used hydrogen bags for lift and engine-driven propellers for steering, began to appear. Airships were used for a variety of civilian and military uses until the 1930s, when airplanes became cheaper, faster and safer.

How did they manage to lower the altitude of the hydrogen balloon in order to land?

They would let out some of the gas to lower the buoyancy.