In 1832, a Japanese cargo ship with 14 people aboard was caught in a storm and pushed out into the Pacific. One of them was 14-year old Yamamoto Otokichi, who was about to begin an unexpected two-decade trip around the world.

In the year 1600, the Japanese warlord Ieyasu Tokugawa defeated his last remaining rival, unified Japan under his control, and took de facto power from the Emperor. Under the title of Shogun (“great barbarian-defeating general”), Tokugawa’s rule was absolute. The only possible threat to his regime (and to the independence of Japan itself) came from the Europeans, and over the next few years, the Shogun took drastic measures. In 1606, the practice of Christianity was outlawed in Japan, and the Portuguese missionaries were all expelled. In 1636, the Shogun carried this further; he not only expelled all foreigners from Japan, but banned any Japanese people from traveling to other countries, or even building a large sea-going ship, under penalty of death. Only one port island, in Nagasaki, was left open to a small tightly-regulated trade with China, Korea, and Holland. The policy became known as sakoku (literally, “locking the country shut”). The Tokugawa Shoguns would rule Japan for the next 200 years, and the islands became the most isolated places in the world.

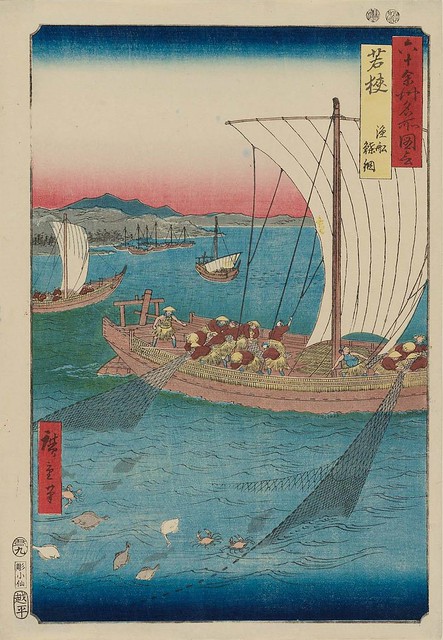

On October 11, 1832, two centuries after the Shogun’s edict, the 50-foot cargo ship Hojun Maru set sail from the tiny coastal village of Mihama, bound for the capitol city of Edo (modern-day Tokyo) with 150 tons of rice and porcelain pottery. On the trip, the little boat was caught in one of the fierce storms that often ravaged the Japanese coast. Pounding waves broke off the mast, and the ship’s rudder was torn off. When the storm ended, the Hojun Maru was adrift in the Pacific, out of sight of land, with neither a sail for propulsion nor a rudder for steering. The 15-man crew was completely at the mercy of wind and current.

For over a year, they drifted helplessly. They survived by eating the rice cargo and catching fish, and by modifying a sake distillery to make fresh drinking water from seawater. One thing they did not have, however, was a source of vitamin C, and one by one they began to succumb to scurvy. After 14 months, only three of the fifteen crewmen were still alive: a 29-year old sailor named Iwakichi, a 16-year old named Kyukichi, and 15-year old Yamamoto Otokichi.

Finally, in December 1833, the floating hulk of the Hojun Maru washed ashore. At first, the sailors thought they had drifted into one of the island groups south of Japan. But when they encountered a group of people, everything about them was different from anything the Japanese had ever heard of. The people were from a band of Native Americans known as the Makah. The crippled Japanese boat had drifted all the way across the Pacific to North America, and were now in a part of the Oregon Territory that would become the state of Washington.

The Makah, in turn, did not know what to make of these odd people who had come from the ocean. They took the castaways to one of their fishing villages and nursed them back to health, then, following the accepted customs of the Pacific Northwest tribes, they kept them as captive laborers.

Over the next few months, stories were passed from tribe to tribe about the three strangers, and eventually the tale, along with a drawing, reached Dr John McLoughlin, a British territorial official in Fort Vancouver. From the pictograph characters written on the drawing, McLoughlin concluded that the men must have come from China, and sent a naval expedition to find them. By the summer of 1834 Otokichi and his two companions were at the Fort. They were taught English by a local clergyman, and once McLoughlin was able to converse with them, he was amazed to learn that they were not Chinese, but Japanese. By this time, Japan had been completely closed to foreigners for over 200 years, and virtually nothing was known about the secretive islands.

Here, McLoughlin realized, was a unique opportunity for the British Government to make contact with the Japanese Shogun, perhaps even leading to diplomatic and trade relations and strengthening England’s position in the north Pacific. In November 1834, McLoughlin sent the three Japanese castaways on the Hudson Bay Company ship Eagle, which was heading for England by way of Hawaii, hoping that Parliament would send a diplomatic mission along with them to Edo. Otokichi, Kyukichi and Iwakichi arrived in London in June 1835.

But the British Government was already entangled with trade disputes in China, culminating in the Opium Wars, and had no room on the agenda for Japan. Instead of sending a diplomatic mission to the Shogun, Parliament took the three Japanese sailors on a quick tour of London and then sent them to the Portuguese port of Macao in China. They were taken in by Karl Gutzlaff, a German working for the British Government as a translator. Over the next two years, the three exiles taught Japanese to Gutzlaff and helped him write a translation of the New Testament. While in Macao, the group was joined by four new Japanese sailors who had just been caught in a storm and blown to the Philippines. There was no attempt to return the castaways to Japan, apparently because they feared that, having lived for so long among the foreigners, they would be killed by the Shogun if they came back.

But in July 1837, an American merchantman, Captain Charles W King of the USS Morrison, appeared in Macao with plans to approach the Japanese Shogun for permission to begin trade voyages. King offered to take all seven of the castaways back to Japan, hoping to use this as a means of establishing contact with the Edo government as a gesture of goodwill. Instead, when the Morrison entered Edo’s harbor, it was fired on by Japanese cannon. King left and tried to enter Japan again, at the port of Kagoshima, but was fired on once more. He managed to contact a local official, who took two of the seven Japanese castaways, but then told King to leave. The Morrison returned to Macao with Otokichi and the four others.

Now 21 years old, Otokichi decided that he would never be allowed to return to Japan, and made a life for himself in China. Moving to Shanghai, Otokichi became a translator for British and American shipping companies, married a Malay woman from Singapore and had four children, became a British citizen, and took the English name John Ottoson. He finally got a chance to visit Japan, only briefly, in 1849, when the British ship HMS Mariner was allowed to enter Edo harbor on a mapping expedition. Otokichi served as a translator: to hide from Japanese authorities who he feared might arrest him, he posed as the son of a Chinese businessman.

The Shogun’s policy of sakoku finally collapsed in July 1853, when US Navy Commodore Matthew Perry led a fleet of warships into Edo and, at the point of a cannon, forced Japan to sign a treaty opening her ports to American trading ships. Other countries followed, and when the British sent a fleet to impose their own trade treaty in October 1854, Yamamoto Otokichi was there as a translator, under his British name “John Ottoson”. It was 22 years, almost to the day, since the 14-year old boy had left port on the Hojun Maru.

During the talks, Otokichi made contact with a number of Japanese officials and was apparently issued a request by the Shogun’s government to return to Japan, but Otokichi chose instead to return to his family in Shanghai. After the treaty, the British Government awarded him a large sum of money, which he used to move with his wife and children to Singapore. He died there in 1867.