No, it’s not a Hollywood scifi movie about a caped superhero . . . In World War Two, the US military had actual plans in the works to use bats–Mexican Free-tailed Bats, to be specific–as living incendiary bombs to win the war by setting fire to entire Japanese cities. It was called “Project X-Ray”. And here is its strange story.

The Bat Bomb

When the radio news bulletins flashed over the air on December 7, 1941, about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, 60-year-old Pennsylvania dentist Dr Lytle S. Adams happened to be on vacation in Carlsbad Caverns, New Mexico–a cave system that was famous for the millions of bats who roosted there each night. Like other Americans, Adams was shocked and angered by the Japanese attack, and wanted to see Japan beaten in vengeance. And as he watched the massive swarms of bats returning each morning to the Carlsbad Caverns to roost, Adams began to formulate a plan . . .

In 1941, Japan was still a traditional society, and traditional Japanese houses were small, packed closely together, and built from wooden frames covered with oiled paper walls. These were cheap, easy to build, and could be quickly replaced in the event they were knocked down by one of Japan’s frequent earthquakes. But, Adams realized, they made Japanese cities uniquely suited to a specific weapon–incendiary firebombs. Drop some incendiary bombs on a Japanese city, Adams thought, and the resulting fires would ignite all the nearby homes and spread quickly to engulf the entire city. It would devastate the Japanese into surrendering.

The best way to do this, Adams concluded, was to simultaneously ignite a huge number of small fires over a wide area, which would then each spread outwards and unite with each other to form one massive sheet of flame to cover the whole city. And after some thought, Adams, inspired by what he had seen on his vacation, came up with an idea for a way to do this–bats. If a container full of live bats were dropped onto the city, each bat carrying a tiny incendiary bomb strapped to it, the bats would all scatter to find hiding places in unseen nook and corners where, when the little firebombs went off, they would spark thousands of small fires all over the area, producing a firestorm which would engulf and destroy the city. To test his idea, Adams managed to catch a few of the bats and did some experiments, finding that the bats were able to fly even if they were carrying three times their own body weight. It seemed to Adams like an entirely feasible idea.

If the idea had occurred to anyone else, it would probably have ended there. But Dr Lytle S Adams had an enormous advantage that few other people had–he was friends with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. On January 12, 1942, three weeks after Pearl Harbor, Adams sat down and typed a letter to the White House.

Eleanor convinced her husband, President Franklin D Roosevelt, that it was a good idea. Roosevelt forwarded Adams’ proposal to Colonel William “Wild Bill” Donovan, who would later go on to head the OSS but was then with War Department’s National Research Defense Committee, in charge of developing new weapons systems. In the accompanying note, Roosevelt declared, “This man is not a nut. It sounds like a perfectly wild idea but is worth looking into.” Donovan in turn sent the idea to bat expert Donald Griffin, who wrote back, “This proposal seems bizarre and visionary at first glance, but extensive experience with experimental biology convinces the writer that if executed competently it would have every chance of success.” In March 1943, the US Army Air Force officially established “Project X-Ray”, which was ordered to “determine the feasibility of using bats to carry small incendiary bombs into enemy targets.” Adams himself was enlisted and placed in charge of the project.

The first order of business was to obtain bats for testing. Initial plans called for the use of the Mastiff Bat, the largest species in North America, which was capable of carrying a full pound of explosive. But these bats were relatively rare and there weren’t enough of them for the numbers needed. Next was the Pallid Bat, which though smaller was far more common–but the Pallid Bat turned out to be too delicate and unable to withstand the physical rigors that it would experience in being dropped from an airplane. Finally, Project X-Ray selected the Mexican Free-tailed Bat, because it was numerous and it could carry a fair amount of weight, and was tough enough to survive the drop procedure. Army personnel with nets went to New Mexico’s caves each night and caught thousands of Free-tailed Bats.

The most difficult task was to design a reliable incendiary device that was powerful enough to start fires in buildings, while still being small and lightweight enough to be carried by the bats. This task went to Dr Louis Fieser, a chemistry researcher at Harvard University who had just invented a flammable jellied gasoline called “napalm”. Fieser came up with two bomblet designs, one carrying 0.6 ounces of napalm, and the other carrying 1 ounce. The devices were attached to the bats with surgical clips, and had chemical timers to ignite them at a preset interval. The bats, of course, were incinerated when the napalm incendiary went off.

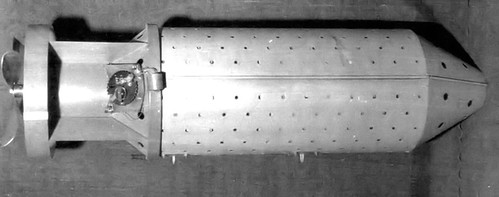

Next, a bomb had to be designed to deliver the napalm-rigged bats. To make the bats easy to handle, they were refrigerated to induce them into hibernation. The immobilized bats were then fitted with their napalm bomblets and placed into the actual bomb, which consisted of 26 round cardboard trays that were divided into 40 little compartments apiece, each compartment holding one sleeping bat. The trays were stacked atop each other inside a cardboard bomb casing. When the bomb was dropped from an airplane, the bomb casing would peel away, the trays would drop apart from each other, releasing the bats, who would then fly off and look for a place to hide in the rafters or attic of a building–where the napalm would then ignite and start a fire. A raid consisting of ten B-24 bombers would be capable of releasing over a million bats. It was estimated that the bat bomb would be able to start fires over an area three times as large as a conventional incendiary bomb.

The first test drop, in mid-1943, failed when the bomb trays broke apart. After some strengthening, the next two tests drops were a success, and it was decided to try a test with live napalm bombs. Unfortunately for the Army, the test worked better than expected–once released from the bomb, some of the booby-trapped bats found their way inside some of the buildings at the newly-constructed Army Air Force base in Carlsbad where the tests were being done, and set them afire. Because the project was classified, the base commander never even knew that his base was the only target successfully destroyed by a bat bomb. At least the mishap demonstrated that the bombs would actually work as planned.

In December 1943, Project X-Ray was taken over from Adams by Fieser and transferred to the US Marines for testing. About 30 tests were done with the bat bombs, culminating in a test drop on a full-size “model Japanese village” built in the Nevada desert. An observer from the National Defense Research Committee reported back, “It was concluded that X-Ray is an effective weapon.”

Further tests were planned for 1944, but before they could be carried out, the project was cancelled. Not only was the bat bomb project becoming too expensive (it had already spent over $2 million), but it was being rendered irrelevant by the super-secret Manhattan Project. In the end, it was conventional B-29 incendiary raids that systematically destroyed Japanese cities, and the two atomic bombs which ended the war.